Alexei Navalny has appeared in court from prison, head close-shaven and face gaunt, and accused Vladimir Putin of attempting to rule Russia "forever" and caring only about "clinging to power".

It is the opposition politician's first public appearance since starting a 2.5-year jail term, seen as punishment for his fierce criticism of the Kremlin.

Navalny spoke via videolink, his prison kit hanging loosely after a recent 24-day hunger strike over his treatment.

His language was as robust as ever.

President Putin was a "king with no clothes", he said, who was "robbing the people" and depriving Russians of a future. Russians were being "turned into slaves".

The judge rejected Navalny's appeal against a fine for defaming a Soviet World War Two veteran who had appeared in a pro-Kremlin video. Navalny said his weight in jail had fallen to 72kg (11.3 stones), the same as he weighed in school.

But even as the Kremlin critic spoke, another court across Moscow was discussing a petition by the prosecutor to ban all his political organisations as "extremist".

Anticipating the court's ruling, Navalny's right-hand man Leonid Volkov announced that some three dozen "Navalny headquarters" were being disbanded, to protect staff and supporters from prosecution.

The offices were set up in 2017 ahead of Navalny's attempt to challenge Vladimir Putin for the presidency; he was barred from even joining the race.

On Monday, the Moscow prosecutor suspended all activity by the offices, pending the court decision. The activities of Navalny's Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) have also been restricted.

"To make it clear, this decision destroys our political organisation in Russia," Leonid Volkov told the BBC this week. He was speaking from abroad, where he has lived since 2019 for safety as he faces multiple criminal charges himself.

"There is no way we can continue to operate in the country," the activist said, adding that the extremism laws carry punishment of up to 10 years in prison.

Activists could face jail

The "extremist" branding would be toxic, as the Jehovah's Witnesses in Russia have found out: since the religious organisation was outlawed in 2017 on the same grounds almost 500 of its followers have faced criminal prosecution. Dozens are serving hefty sentences.

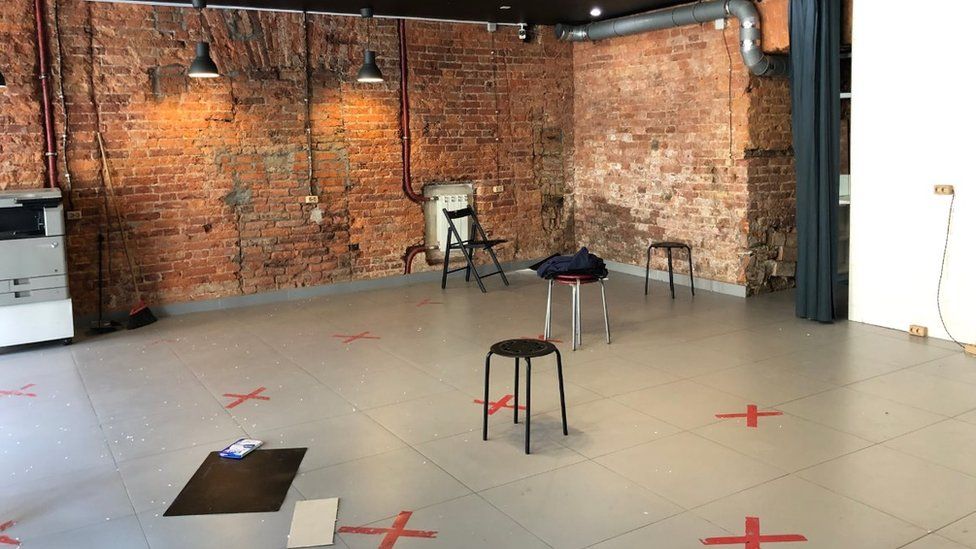

So, across Russia, staff who once worked for Team Navalny have rushed to clear out their offices and delete social media accounts and chats.

In St Petersburg, where supporters queued round the block four years ago when the politician swept into town to open his first regional headquarters, there is now no sign his team were ever there.

The front door of their office is shuttered. Inside there is just a couple of chairs, a coat rack and a printer gathering dust.

Fear of prosecution

Irina Fatyanova, who ran Navalny's St Petersburg team until Monday, stresses that she has now severed all ties with the organisation, at risk of being labelled an extremist.

But she says pressure from the authorities had increased steadily since January, when Alexei Navalny returned to Russia after recovering from a nerve agent attack in Siberia. Arrested on arrival, he has been behind bars ever since.

"Since January, I don't think there's been one calm day when I didn't worry about a knock on my door, or some criminal case," Irina confided, telling me she had been followed, detained and had her house searched in recent weeks.

But the "extremism" label takes the danger to another level.

Irina describes the move as a personal tragedy and now plans to try running for local election, independently of Team Navalny - a plan Leonid Volkov suggests may be replicated across the country.

"Things are frightening, but what happens if we're all scared off?" Irina reasons. "I don't want to look the next generation in the eyes and be ashamed."

But the strength of Alexei Navalny's movement was two-fold: his charismatic leadership and the structure he put in place, supporting activists across the country.

Mobilising via social media, they have staged street protests, promoted anti-Kremlin candidates for election and conducted anti-corruption investigations against top-level officials that have gone viral.

But tolerance of their activities has ended.

In St Petersburg this week, even a wall painting of Alexei Navalny lasted just four hours before police arrived, followed swiftly by municipal workers with daffodil-yellow paint.

Within moments, Navalny's image was obliterated.

BBC