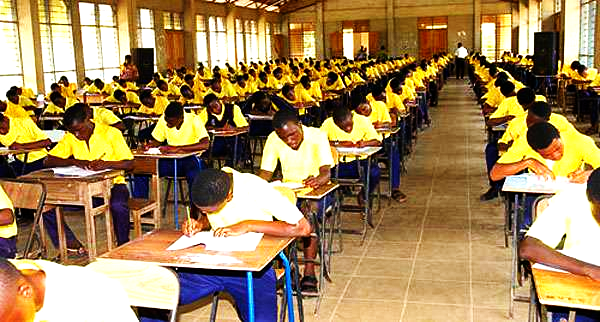

The poor 2016 West Africa Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) results are mere embers of the larger problems associated with the traditional academic type of education.

The scores

The WASSCE results in the Daily Graphic of August 12, 2016 showed that in Integrated Science, while 113,933 pupils (out of the total of 232,390) achieved the acceptable scores of A1 – C6, some 75,938 pupils obtained the unsatisfactory scores of D7 – D8, and 42,519 failed completely. The majority of the candidates - 51per cent - were in the bottom two brackets.

The scores in Mathematics were worse: while only 77,108 pupils (out of 231,592) scored A1 – C6, the greater majority - 67per cent were in the unsatisfactory (D7 – E8) and failed brackets. Though the scores in English and Social Studies were not as bad as Science and Mathematics, generally speaking, the cumulative scores prohibit the majority of the WASSCE pupils from advancing to the next higher stage.

In Ghana, we use summative exam scores for punitive purposes by casting the blame on the failing youth; most of the candidates are tossed to their own devices, with a good number spilling onto the streets, hustling with vehicular traffic for a living. When exam scores, on the other hand, are used meaningfully as formative assessments, we are obliged to ask the pertinent questions: Why and how did such large failures happen? And, most importantly, can’t there be superior alternatives in education that can better serve the youth?

UCC and UEW

Such problems cannot be solved with the same minds that created them in the first place. So let’s consider two things: Even in the academics, starting from the BECE, why, for example, are the basic schools in the Central Region recording some of the worst BECE results when the nation’s two top teacher training universities (University of Cape Coast (UCC), and University of Education, Winneba (UEW) are both situated right there? It’s clear that a good number of the teacher-trainers themselves avoid the dusty unattractive public schools sites, and are more comfortable in the ivory towers of lecture halls and theories than connecting with the student-teachers and children at the locations where the real action is needed most.Â

Who would trust medical doctors and nurses taught in lecture halls, away from professional practice and supervision in the clinics and hospitals? Just as patients are the real concerns of doctors, so must the pupils in the classrooms be the focus of all teacher training centres across the country. Using my own experience as an example, only through the verification of years of full-time teaching in classrooms, were my teacher credentials finally awarded and certified in the US. Â Quality teaching is hands-on, not theory.

There must be reasons for the mass academic failures. In Science, for example, why is the subject taught in Ghana as mere theories? Why is the subject not taught in practical ways in each of the districts for the pupils to see the real purposes and benefits of science? Many people are practical kinesthetic learners, anyway; they do better through hands-on approaches than sitting and memorising abstractions. From primary to the tertiary levels, the lack of applications is the regal albatross that hangs down the neck of education in poor countries. Why choose to glorify theories and morning prayers, but disdain the blessings of action and work that make the theories and prayers come alive.

Education for employment

The Graphic report (August 17, 2016) that “Ghana needs 300,000 jobs annually†is a caution seething openly. Between now and 2020, unemployment - where about “48 per cent of the youth between 15 and 24 years†are jobless - must be a serious concern. Then, of course, the jobs must be created in the first place, in the districts, starting with projects that benefit from the applications of science.Â

A report by the Savannah Accelerated Development Authority (SADA), for example, reveals countless possibilities in the districts in the northern savannas alone.

Kintampo North Municipal stands to gain from maize grain and corn flakes processing. The Kintampo South District can benefit from ginger projects. The Pru District has prospects in cage fish culture. Sene West District – soya and rice production. Bunkpurugu Yunyoo – Soy beans and dried mango processing for both export and local consumption. Central Gonja – Commercial fish farming; Mion District – Shea nut production; Nanumba South – local pottery, cassava flour and yams. Savelugu and Nanton – acquaculture and fisheries. Tolon – fish farming along the Volta. Yendi – beekeeping and Guinea fowl rearing. Garu-Tempane – watermelon and onions. Kassenanankana – piggery. Nabdam – Shea soaps. Talensi – tomato and other vegetables along the White Volta. The list is endless for job creation in each of the 200 or so districts in Ghana, from north to south.

It pays to recall the Singaporean visionary, Lee Kuan Yew’s visit to Ghana in February 1964: He lamented the shortsightedness of Ghana’s policy elites trapping their best and brightest brains behind desks memorising declensions and conjugations of Latin and Greek nouns and verbs, but ignoring agriculture. Education in Ghana is at that inflection point now where it’s clearly senseless to continue on a trajectory that is wasting the potential of the youth, and impoverishing a country endowed with such great prospects.Â

Modern curricular objectives

As William Shakespeare put it in “King Learâ€, “We are not the first who with the best meaning incurred the worseâ€.  But going forward, purposeful education must offer transformative opportunities that address the following key questions: One, does it help to create jobs? Two, does it add value to the nation’s natural endowment and local inputs? Three, does it help the youth to fill existing jobs that require the use of modern technology? Four, does it teach and support the youth to be entrepreneurs who make it by solving existing national and international problems?

For those wonderful things to happen, teachers - across the spectrum, both at the basic and tertiary levels - must upgrade themselves to teach to those needs. Of worthy concern is the large mismatch between what schools prepare students to do to graduate and the practical realities of life after graduation.