On Sunday, citizens of Guinea and the Central African Republic (CAR) will go to the polls to elect their presidents for terms of office of seven years.

Both contests could, in theory, go on to run-off ballots. Yet in both, the incumbents are strong favourites, with observers predicting they will clinch victory outright in the first round with more than 50% of the vote.

But that's where the similarities end.

The CAR, vast and landlocked, is one of Africa's poorest countries, marred by chronic instability for decades, with a succession of armed groups motivated by a variety of local grievances, opportunities for racketeering or political ambitions.

From 2013 to 2016 it was only the intervention of African, French and then UN peacekeepers that averted a slide into deeper inter-communal violence.

The national government in Bangui, the riverside capital on the southern border, just across the water from the Democratic Republic of Congo, has often struggled to assert its authority in the distant outer-lying regions of the north or far east.

Despite these enduring fragilities, multi-party politics has mostly survived, with a fair degree of tolerance for opposition and protest.

There is a sense of national identity and this year has seen two of the most significant rebel groups drawn back into the peace process and starting to disarm and demobilise.

The country has a pioneering special court for trying human-rights crimes, staffed with a blend of national and international judges.

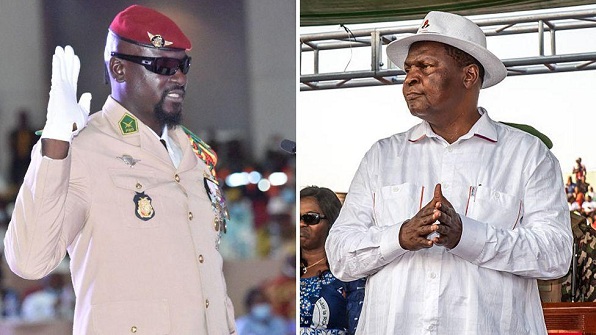

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesPresident Faustin-Archange Touadéra is a mathematician and former university vice-chancellor.

He entered politics as prime minister under the putschist-turned elected head of state, François Bozizé.

Later, after a chaotic interlude of rebel rule and an uncertain transition, he was elected head of state as a post-conflict and consensual civil-society figure.

Today, approaching the end of his second term, Touadéra is seen as a far more political and partisan figure.

He bulldozed through constitutional reform to scrap term limits, allowing him to stand again. This has provoked a boycott by much, though not all, of the opposition.

Yet, contrary to widespread expectations, his most prominent electoral rival, Anicet-Georges Dologuélé, has been allowed to take part in the electoral race.

This contrasts with the situation in Guinea, on Africa's west coast, where Gen Mamadi Doumbouya, leader of the September 2021 coup that deposed the 83-year old civilian President Alpha Condé, is now preparing to convert himself into a constitutionally elected ruler.

Although Doumbouya will face eight challengers at the ballot box, he has dominated the campaign, with his image plastered all over the streets of Conakry, Guinea's capital city.

The most prominent opposition figure of the past 10 years, Cellou Dalein Diallo, with a big personal following among the large Peul community who account for about 40% of the electorate, has been excluded from the contest.

Despite these constraints on the political choice presented to voters, the return of an elected government will come as a great relief to the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas), a regional bloc that promotes economic integration, democracy, and military cooperation among its members.

Almost a year ago, it suffered a blow with the withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger after the military regimes that had seized power in a wave of coups between 2020 and 2023 refused to comply with the bloc's demands to commit to clear timeframes for the restoration of civilian rule.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesDoumbouya made a different choice.

Although he kept good relations with the junta in neighbouring Mali, he has pursued a methodical constitutional review, which has laid the ground for Sunday's vote, even if this has been delayed for longer than Ecowas originally wanted.

His approach to international relations also contrasts starkly with neighbouring regimes, who have cultivated close security ties with Russia and repudiated their previous close partnerships with France.

Doumbouya has maintained good relations with Western governments, particularly Paris. Officials in Conakry praise the French Development Agency as one of their most supportive partners.

Indeed, from the outset, the Doumbouya regime has been treated rather gently by both France and the West generally, and by Ecowas, despite a troubling human rights record.

His overthrow of Condé - who had staged a dubious constitutional referendum to allow himself the chance to stand for a third term and had overseen frequent bouts of security force brutality - was celebrated on the streets of Conakry and barely criticised abroad.