An outcast from birth, Milton Washington is the child of a Korean woman and a black US soldier, who became a "slickyboy", or child thief, and dreamed of making it to America. At the age of eight, he seized his chance.

When a beautiful car pulled up one day outside St Vincent's orphanage in South Korea, Milton Washington made a split-second decision that would change the course of his life.

A black American couple stepped out. The man was in military uniform, the woman had an Afro and wore a beautiful flowing dress, and when Milton realised that they were going to adopt his friend Joseph - who was black and Korean just like him - he ran to the couple's car, jumped inside and locked all the doors.

Crying and screaming for his life, he wasn't getting out unless the man and woman took him home with them too.

The couple - Captain and Mrs Washington - agreed to take both Joseph and Milton home, but only to see which of them fitted in best with their family.

They would give it a few days, they said, and then make their choice.

That night, lying in bed in an unfamiliar bedroom, in an unfamiliar house at the Dongducheon American military base, little Milton made his second big decision of the day - and ran away.

"I didn't want to get taken back to the orphanage - maybe they wouldn't choose me," he says.

"I was just trying to get to America."

Before his life in the orphanage, Milton was the only black child in a small village near the border with North Korea. Milton's father, an American soldier, was long gone, but his mother, who worked hard days in the rice fields, loved him and protected him fiercely against the prejudice they encountered.

The children in Milton's South Korean village would sing a song about red apples, bananas, a train - and a monkey. "I remember the part of the song they sang to me the loudest. The part about the black monkey's butt being red. That set the tone," he says. It was just an innocent playground song on the face of it - it wasn't racist, or at least, not designed to be. But they turned it into something hurtful: a way to single him out for the colour of his skin.

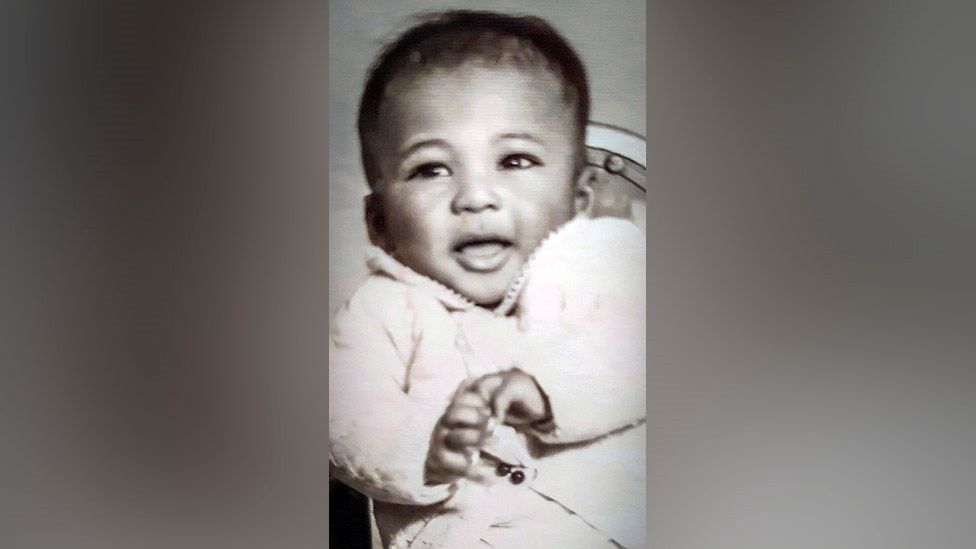

Milton as a baby - he does not know his exact year of birth

Milton knew that his father was from the US - in his mind a land of flying cars, where the cities were made of gold, with ice-cream mountains.

"I dreamed of going to America because it was full of black people - these magical creatures," Milton says, "and of being accepted."

Milton's America was a fantasy land that couldn't have been more different from his reality. He and his mother lived in a mud and stone hut, slept on the floor, and washed their clothes in the river.

One morning, village elders arrived at the door and told Milton's mother they would no longer accept "the shame that you're bringing upon this village because of that boy". Although Milton's mother argued their case, she and Milton left their home and moved to a nearby town attached to an American military base. There were cars there, electricity, and money, all of which were new to Milton - salt had been the currency in their village.

Milton also saw black American soldiers for the first time, and felt a step closer to finding his father.

In the alleys of the red-light district below their tiny apartment, homeless boys begged, picked pockets, and fought with other gangs.

The American soldiers called them "slickyboys" - slang for little thieves. And when six-year-old Milton shared a packet of Oreos with the boys - given to him by his mum's American boyfriend - he became a slickyboy too. Milton finally felt like he belonged.

"All the black soldiers would give me money - dollar bills, not just change," he says. "It completely changed my life."

Milton's mother had become a sex worker in a club in town and went out at night to work. Milton was left alone in their apartment - under strict instruction not to leave, instructions he routinely ignored.

One night Milton's mum didn't return from work as expected - the club had been raided by the police and she and all the other women who worked there were sent to jail for two weeks.

Free of his mother's rules, Milton and his friends ran wild, stealing drinks from bars and having adventures all over town.

When his mum returned, she made sure Milton was never left alone again. Each time she got wind of a police raid, she would drop

Milton at an orphanage for a couple of weeks so that he was safe.

Milton remembers being racially abused by the other, mostly Korean, kids at these orphanages, as he had been in the village growing up. But this time, he didn't let it get to him.

"I would almost laugh it off," he says. "'Yeah, I may be these racial slurs that you're talking about - but you're the orphan. I have a mother, she says she's going to be back in two weeks.' And she was always back in two weeks."

For a while, this routine continued. Then one morning, Milton and his mum took a taxi to a different orphanage, where many of the children looked like Milton. It was an orphanage for children born to American servicemen and Korean mothers, called the St Vincent's home for Amerasian children.

Milton's mum assured him she'd be back the following day and promised him a present - he asked for a train set. But when she returned there was no train set, just a hug that he didn't know meant goodbye.

"She told me, 'I need you to be strong,'" he says. "That was the last time I saw her."

Short presentational grey line

It wasn't long after Milton first arrived at St Vincent's orphanage that Captain and Mrs Washington took him to their home on a military base - from where he decided to run away.

He didn't get far. He was still small and the compound fences were high, and a search party found him, hours later, sound asleep in a children's playground.

But the incident shook the Washingtons, who decided that both Milton and Joseph could stay with them permanently. The boys were adopted in 1977 and eventually moved to America - becoming part of a noisy, loving family of six children, who rode bikes, played sports, and went to school - all the normal childhood things Milton had longed for.

But he worried about what had become of his mother and would cry himself to sleep. He was haunted by dreams of wading through paddy fields looking for her. She had always been his "island of refuge in a very tough world", he says.

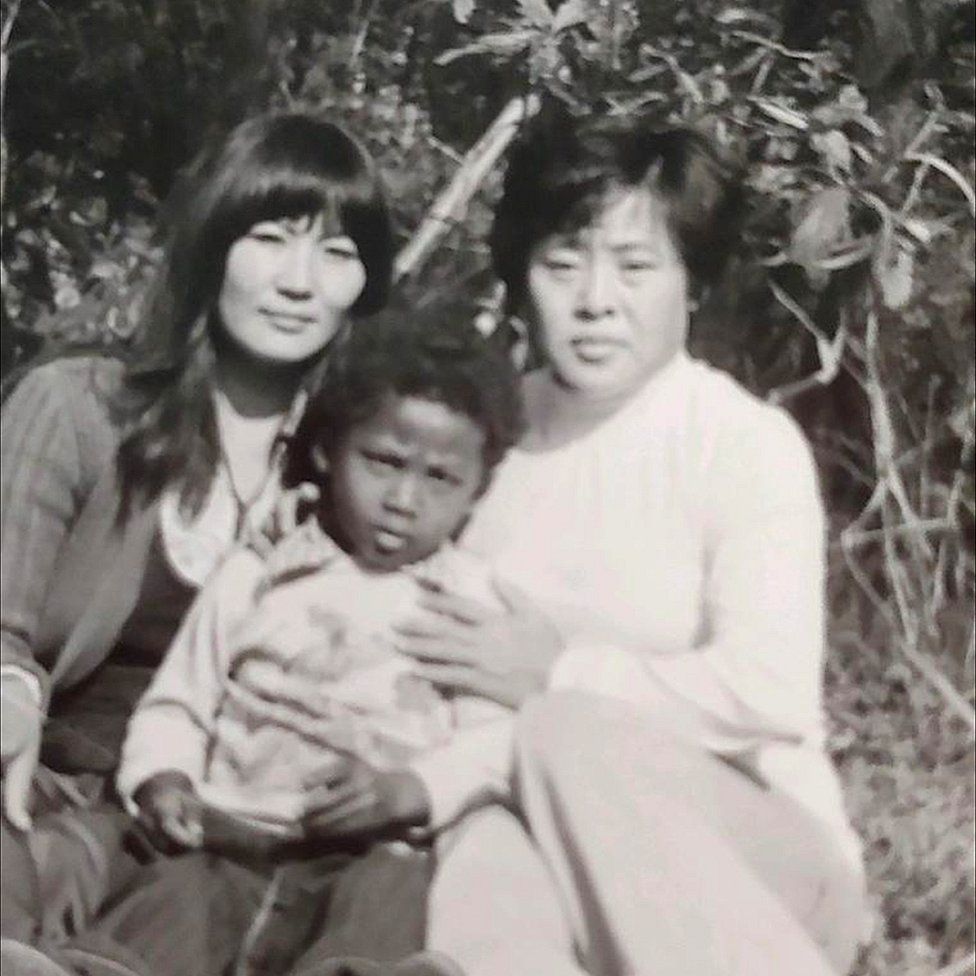

Milton at his 10th birthday party with his adoptive mother, Gwendolyn Washington

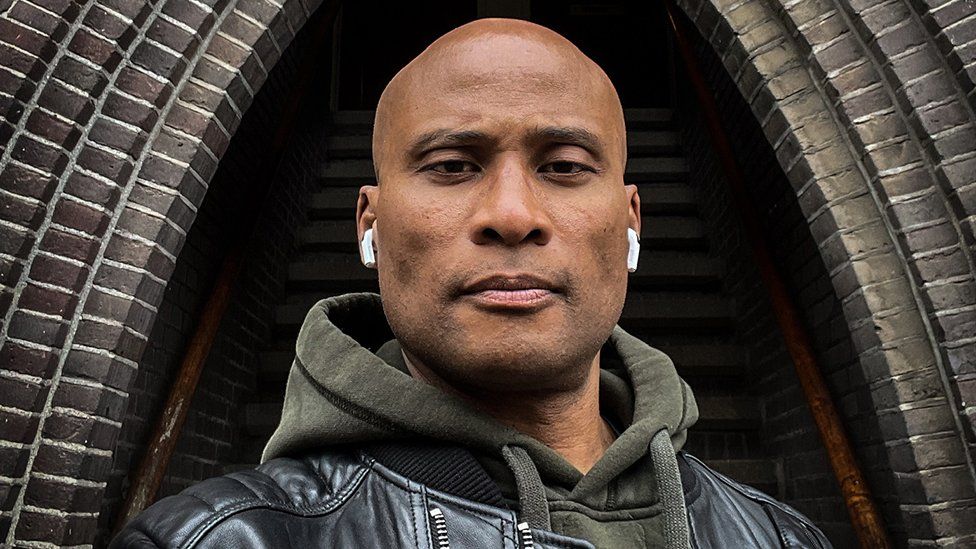

Now in his 50s - he's not sure of his exact age - Milton works as a photographer in New York and is writing a memoir called "Slickyboy".

He's always remained curious about his biological family, and in recent years began to look for connections via DNA websites. In April 2019, he got a hit. It was a family member on his mother's side, who wanted to speak to him immediately.

"Hello, I'm calling from Seattle," the voice - with a strong Korean accent - said.

"This is Milton-ah (little Milton)," he said, using the name his birth mother had often called him.

"I am your sister, Tong, do you remember me?"

Milton did remember meeting Tong - she was one of his older sisters, and they had met a handful of times in Korea when Milton was a little boy. Tong had lived with their grandparents, from whom Milton's mother was estranged.

Speaking to his half-sister, Milton says, was "an incredible moment".

"I was just really excited [to be] connected with my past, and to have my memories validated by her."

Milton with his sister Tong and their mother, Park Young-Ja

Milton had not expected his mother to survive, but Tong told him she'd lived a long life, and had died just a few years previously. His mother and sisters had come to the US in 1998, and though they knew that Milton was living there too, Milton's mum had felt she had no right to contact him.

But she had left a keepsake for Milton with Tong - a gold and jade necklace to remember her by.

"It's a beautiful piece," he says. "It's a way to carry my mother with me."

Milton Washington says people are often surprised to hear he is Korean

Milton keeps searching for answers about his father. He believes his dad likely came from Louisiana, but has little more information.

"I want to know what kind of man he is. He's the only missing link," Milton says.

Despite the sadness he still sometimes feels, Milton is certain his mum made the right decision giving him up all those years ago.

"She knew that if I had a shot at an American life, I would do well at it. I love her for that act," he says.

"There is a hole in my heart that's always going to be there. But the benefits of my current life versus what it could have been - there's no argument there."

BBC